Sounds to Me Like A Promise: On Survival

Lex’s contribution to The Feminist Wire‘s forum on Black Women’s Health in the Academy

(after Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years by Dagmaar Schultz)

“I love the word survival, it always sounds to me like a promise. It makes me wonder sometimes though, how do I define the shape of my impact upon this earth?”

–reflection cut from an early draft of “Eye to Eye: Black Women, Hatred and Anger” by Audre Lorde (Audre Lorde Papers, Spelman College Archive)

I love the word survival. And I hate how we declaim it in our contemporary mouths. Rarely these days do you see the word survival without the disclaimer, not just (survive) and the additive, but thrive. Are we so seduced by the rhyme that we forget the whole meaning of survival? What people most seem to be actually meaning today when they say, “not just survive” actually means not just subsist. Survival has never meant, bare minimum, mere straggling breath, the small space next to the line of death.

Survival references our living in the context of what we have overcome. Survival is life after disaster, life in honor of our ancestors, despite the genocidal forces worked against them specifically so we would not exist. I love the word survival because it places my life in the context of those who I love, who are called dead, but survive through my breathing, my presence, and my remembering. They survive in my stubborn use of the word survival unmodified. My survival, my life resplendent, with the energy of my ancestors, is enough.

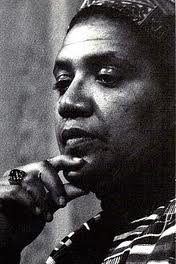

Of course survival is a keyword in black lesbian poet warrior mother teacher, Audre Lorde’s lexicon, and in our memory of her. Ada Griffin and Michelle Parkerson’s biographical film about Lorde is called “A Litany for Survival” after her most remembered and recited poem. “A Litany for Survival” is in fact the poem through which Lorde most frequently survives and is often the last shrine of the word survival on our tongues.

So it is no surprise that Dagmar Shultz organizes her film, Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years, around footage of Audre Lorde powerfully reciting this unkillable poem, stretching the reading through the entire film, but not just because the poem is iconic. The persistence of the poem is appropriate because the film is 100% about survival.

The film is the survival of Audre Lorde, her face given back to us through the many portraits interspersed in the film. The film is the survival of the Afro-German women’s movement as we watch the living founders of that movement, silver-haired and sleek, comment on their own young gumption more than 20 years ago. The film is the survival of May Iyim, a poet and co-founder of the Afro-German woman’s movement who killed herself at the age of 34, four years after Audre Lorde died. I find it appropriate and moving that Iyim gets the most face time of anyone in the film (besides Audre Lorde) and is also memorialized with a series of portraits, even though viewers who don’t know about Iyim’s life and death, which the film does not explicitly contextualize, may not understand why her bright face is such a crucial image. The film is the survival of an intergenerational ethos, both in the work of Iyim and other Afro-German women, often raised in white families, to make intergenerational ties, and in Audre Lorde’s reminder that “no revolution happens within one lifetime.”

The film is the survival of Audre Lorde, her face given back to us through the many portraits interspersed in the film. The film is the survival of the Afro-German women’s movement as we watch the living founders of that movement, silver-haired and sleek, comment on their own young gumption more than 20 years ago. The film is the survival of May Iyim, a poet and co-founder of the Afro-German woman’s movement who killed herself at the age of 34, four years after Audre Lorde died. I find it appropriate and moving that Iyim gets the most face time of anyone in the film (besides Audre Lorde) and is also memorialized with a series of portraits, even though viewers who don’t know about Iyim’s life and death, which the film does not explicitly contextualize, may not understand why her bright face is such a crucial image. The film is the survival of an intergenerational ethos, both in the work of Iyim and other Afro-German women, often raised in white families, to make intergenerational ties, and in Audre Lorde’s reminder that “no revolution happens within one lifetime.”

The film is about survival. It is Lorde clarifying that “survival is not a theoretical problem and poetry is part of my living,” and offering concrete advice for the survival of Afro-German women’s groups and literary projects despite the difficulties they face. It is Lorde schooling white women on the urgency of their growth in the face of a 1990s neo Nazi climate in Germany explaining that “it is not altruism but survival” that requires them to act.

I appreciate the existence of this survival film, and in the context of our current forum on Black women’s health in relationship to the academy I think it offers several lessons. One of course, is the place I start, with the reclamation of the word survival. Survival is what some Black women do in the academy, not because they are barely alive, but because we are not supposed to do it, and sometimes we do it anyway. And the way we do it matters.

The survival of Black feminist intellectuals, which happens within or without the academy, is our intentional living with the memory of May Iyim’s suicide after being in a mental institution; our living with the knowledge that as Audre Lorde’s archival papers prove, she was denied medical leave, had to turn down prestigious fellowships (including the senior fellowship at Cornell) that required residency in places too cold for her to live during her fight against cancer. The English Department at Hunter, which recently honored Lorde with a conference 20 years after her death, rejected her proposals at the end of her life to teach on a limited residency basis that would allow her to teach poetry intensive classes for students during warm weather in New York and to live in warmer climates during the winter based on her health needs.

If Audre Lorde’s proposal to teach in a way that allowed her to survive can be denied by the City University of New York, even as she was simultaneously selected as the New York State Poet Laureate, what does that teach us about the value of our bodies in the spaces that tokenize our minds?

And of course this is not unique to Audre Lorde. June Jordan’s records show that even as she was battling breast cancer, UC Berkeley would not grant her medical leave or the breaks from teaching that she repeatedly wrote her administration to request in 2001, months before she died, less than two years after her Black feminist Berkeley colleague, Barbara Christian died. This is not ancient history. This is 21st century economics and the austerity measures, scarcity narratives, and exploitative practices of the university have only gotten more severe with time.

And of course this is not unique to Audre Lorde. June Jordan’s records show that even as she was battling breast cancer, UC Berkeley would not grant her medical leave or the breaks from teaching that she repeatedly wrote her administration to request in 2001, months before she died, less than two years after her Black feminist Berkeley colleague, Barbara Christian died. This is not ancient history. This is 21st century economics and the austerity measures, scarcity narratives, and exploitative practices of the university have only gotten more severe with time.

Let us be clear. Universities keep huge endowments, money on reserve, because they are supposed to keep money. They will always tell you they cannot afford you. They will not spend their money to save the life of a Black feminist. Poet Laureate though she may be. Let us be clear. The universities that we mistakenly label as our bright quirky only refuge for Black brilliance have worked our geniuses to death, and have denied us help when we asked for it. The universities that employed June Jordan, Audre Lorde and so many others, watched cancer eat away at our geniuses, as they simultaneously ate away at black women’s labor. An institution knows how to preserve itself and it knows that Black feminists are more useful as dead invocation than as live troublemakers, raising concerns in faculty meetings. And those institutions continue to make money and garner prestige off of their once affiliated now dead faculty members.

The university was not created to save my life. The university is not about the preservation of a bright brown body. The university will use me alive and use me dead. The university does not intend to love me. The university does not know how to love me. The university in fact, does not love me. But the universe does.

Survival is what Audre Lorde calls “a now that can breed futures/like bread in our children’s mouths/so their dreams will not reflect the death of ours.” But we, Black feminists of my generation navigating our relationships to the academy, are the children. And we must not ignore the lessons of our ancestors, nor the futures that they have made possible to us through their creativity and persistence.

Should I take a tenure track job anywhere in the world among any manner of quiet or loud racists just to have the security of a health care plan that will become more useful every year because of the stress and ideological violence I suffer on the job? Does it honor my ancestors for me to uproot myself from the communities that have nurtured me that are my realest sources of sustenance and that I must also sustain with my presence and my love? Did Audre Lorde and June Jordan teach in prisons, coffee shops, living rooms and subways so that I could pretend that the university has all the real classrooms and everything else must be a side hustle?

These are the questions I asked myself as I held those denied requests for medical leave in my hands. And again as I turned down tenure track jobs.

And I decided that Audre Lorde is right. Survival is a promise. It is not a promise that any university or non-profit organization can make to me. It is a promise that I make with my currently breathing body to the ancestors who move through it. It is a promise I make in honor of the deaths that make this clarity not only possible, but unavoidable. Survival is a promise. Which is why I am living an experimental intellectual life, dedicated to the creation of accessible autonomous school systems, (in the living room and on the internet—blackfeministmind.wordpress.com) that bring the work of Black feminist ancestors and elders to our communities, directly and committed to creating collective systems of health and mutual support that allow our genius to be accountable to, accounted for, sustained by and shared by the unendowed oppressed communities that are the source of all genius and transformation. Survival is a promise. A covenant between my ancestors, my living communities and this body that is 100% composed of the love that connects them.

I am still working it out. I am uninsured and unaffiliated and living a life that overflows with love shared across space and time. I survive, not because I am barely alive, but because I am flagrantly alive in the sight of my ancestors. The universe loves us. And we sell ourselves cheap when we forget. Our ancestors are teaching us what we deserve. May we never sell our legacy for a mess of ego and scholar-styled swag. May we refuse to exploit our legacy in order to earn more exploitation. May we remember who we are. The shape of Audre Lorde’s impact includes her achievements, her words, her losses and everything she went through that we should not repeat as if we did not know.

I love the word survival. It sounds to me like a promise worth keeping.

Extra

Lex’s Comments for the Panel on “Extra-academic work” in the Duke University English Department Graduate Students Professional Development Series

There was a housemate I had in college named Charles* who was ostentatious and performative. Louder than necessary, full of drama and somehow he had three laptops and designer cases for all of them. And every so often someone would say “Charles you are so extra.” Which now in hindsight I realize meant that he was queer, an excess to the situation that would not allow the situation to be content with what it was. And now not even ten years later, I myself a self-identified queer black feminist troublemaker am spiritually rejoining Charles on this professional development panel appropriately designated “extra.” Which means I have to say something about the context that I am speaking from because it is, evidently queer to the context in which we are speaking together today.

What is called here “the extra academic” I call the “community accountable intellectual” not necessarily organic, and possibly even genetically modified. So I have to explain who I am. And maybe like Charles, be more explicit than necessary. Since I am queer, you have the privilege of pretending to ignore me for the sake of whatever norms you have bought into or are investing in now. The economy in which the type of labor that I do, founding a multi-media amplified community school called Eternal Summer of the Black Feminist Mind and co-creating a national experiential archive called the Mobile Homecoming Project which amplifies generations of Queer Black Brilliance, is designated as extra is a particular kind of economy, sometimes invisible to itself, in which knowledge is a product for sale within a self-reproducing hierarchy of ideas inside a corporation where particularly offerings of accountability to particularly situated communities (say departments, undergraduate students, academic publishers) are counted and rewarded as loyalty.

When Judith Butler talks about accountability (and I am only bringing Judith Butler into it because I am in this particular room, accountable to you as a potential community) she follows Nieztche to a juridical scene where accountability emerges in the moment where someone has to explain or take responsibility for a wrong. So I am here giving an account of myself and I why I did the wrong thing with my PhD and turned down tenure track job offers in friendly departments to instead open a community library and intergalactic ritual classroom and get in a very old RV stalking old black queers across the country. But I think about accountability differently and I think the only harm that I may have done may be to those people who find their jobs and prospects more acutely boring in my presence. And even that wrong I hope will eventually become a favor.

When I break down accountability myself, I end up in a different scene. The scene of a storytelling circle where I may be called to explain my decisions, what I have done with my time, who have I touched and who I have ignored to a community of comrades, ancestors and possibilities who are engaged in the same process of making love actual. The micro-institution building that I have been doing with the Eternal Summer of the Black Feminist Mind and the Mobile Homecoming Project is an experiment inside of capitalism in seeing how much overlap I can make between those to whom my story belongs out of love and those who determine what happens to my bank account, and food and health resources. But I end up agreeing with Butler when she says that no accountability is complete. We cannot fully give an account of ourselves. I remember that Charles was often ignored, ridiculed. Even in our house, which was supposed to be such a safe space for black students on campus. I remember there were weeks where Charles refused to eat anything but cheez-its and I, living with him felt powerless confused and worried about what he was doing with his life. I thought it would be a healthier safer thing for him to conform in certain ways, or at least to do a better job of pretending.

And during the time that I knew Charles, who stole designer clothing and bags, I was stealing food and bottles of naked juice from the business school on campus to express my resentment and learning how to steal my time through a strategic relationship to the University. I wish I could be an organic intellectual, but right now about a third of what I eat is grown and made by my community and the rest of it has Monsanto somewhere on it. I have a PhD in English from Duke with a bunch of forms signed by another thief, you may have met Fred Moten (link university and the undercommons). And in a system where our time is stolen into the unequal production of life in deathscale, I am not ashamed of stealing my time and shuttling it into the spaces that I think it is most urgent. I am not ashamed of bringing whatever I learned in the archives into living rooms, nightschools, tea ceremonies and side of the road conversations first even though that’s not who first paid me to do it in dollars. Or to admit that the major skill I gained here in this university was the technology of explaining myself and my decisions to whoever might ask for an account, or of deferring and evading it seamlessly.

Most people remember that Audre Lorde, whose words I bring into every room, said that the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house, and forget that she said right afterwards that that truth was only threatening to those people who still thought the master’s house (meaning the university) was their only possible source of support. So in the name of the Lorde and in the name of Charles who sat in this room once, and who applied for this degree and didn’t get in, I am a late capital Maroon, cultivating threatening alternative sources of support, occasionally stealing from the plantation. Or in the terms we agreed upon for this conversation. So very extra.

*Not his real name.

*********

Off-the-Hook Black Feminist Mentorship: An Anti-Capitalist Re-evaluation

by Alexis Pauline Gumbs

(first appeared at http://thefeministwire.com/2011/12/off-the-hook-black-feminist-mentorship-an-anti-capitalist-re-evaluation/)

A lot of times, June Jordan couldn’t pay her phone bill. I held the disconnection notices in my own hands, sitting hungry and enthralled in the Black Feminist poet, educator, revolutionary’s papers in the Schlessinger Archives at Harvard.

That morning I rode the train from my sista-friend’s grandma’s house in Roxbury, where she fed a block-full of cousins out of her amazing garden/urban orchard cattycorner from a poison-filled produce-empty cornerstore into Cambridge, where the police-violence-bought white privilege on the faces of the students and passersby made me want to slap a white person. Trust June Jordan to bring me to a place of rage.

I sat contemplating what set of circumstances allowed me to be sitting up at Harvard looking at June Jordan’s phone disconnection notices and folders filled with letters where people mentioned that they tried to call her but couldn’t get through. And I thought of at least two things:

- What immediately made my trip to Harvard to be the very first researcher to visit June Jordan’s papers possible, after harassing the kind archivists every day until they confirmed that the papers were processed and ready to view was the hospitality of Bonita’s grandma: an old Black food-growing woman who rarely left Roxbury, focused on feeding generations of her family love-grown food that might counteract the draining poison of Boston’s intense racial violence.

- And the obvious gratitude goes to June Jordan herself, who believed that telling the truth, and being where her people and the future we deserved needed her to be was more important than knowing she could pay bills on time. There were times she didn’t have food for herself and her son over everslow honoraria checks and writer’s fees. She was honest about it in her collection Civil Wars. A Black single mom not knowing if she could give her kid Christmas or even heat the apartment.

And the same love, risk, and accountability demonstrated by Bonita’s grandma and June Jordan is what makes this moment possible for me as a community-accountable scholar, teacher, and artist. So what does this have to do with mentorship?

I am telling you this to explain why, in this forum on mentorship on a website created by and mostly read by Black Feminist university-engaged scholars, I am skipping over the many cherished mentors I have within the academy and the publishing and archiving worlds. I am skipping over wonderful people who have raised me, fed me, affirmed and inspired me, to talk instead about the mentors with whom I have grown vegetables in the erstwhile tobacco dirt of North Carolina. Today I am not focusing on my mentors who are nerd-famous uber-published senior named-chair Black Feminist academics and administrators (and who honestly complain in weary voices about how many of us young scholars demand their mentorship). Instead, I am focusing on those mentors who have had such a major impact on my everyday life here in Durham and the decisions that have taken me to recreate the meaning of community accountable intellectual, spiritual love infused education and rooted artistry.

Today I want to tell you about Mama Nayo and Mama Nia, who I preface with “Mama” less for cultural nationalist throwback reasons than for the fact that like my mother, they are deserving of more respect then I can generate every time I say their names. Mama. Because they have a rebirthing influence on my days, and these are the off-the-hook mentors I want to tell you about in the name of June Jordan’s disconnected phone.

Mama Nayo Barbara Watkins, now an ancestor, was a Black Arts South warrior and healer. Power poet and acclaimed people’s playwright, she used interactive theater to facilitate communities telling the submerged histories of their own struggle and triumph. She created an educational center for parents and children learning through learning disabilities in the name of her son. She worked to make Black artists central to Alternate ROOTS, an arts and activism organization supporting Southern artists. Mama Nia Wilson heads SpiritHouse, a local organization using arts-based interventions to lift up the spiritual and critical strategic leadership of the people most impacted by the prison industrial complex here in Durham, running a community center and several programs out of her home and scraping funds together to bring youth leaders around the country to learn about the connections between oppression and brilliance everywhere.

I am not writing this essay so that these mentors will know how much I love and admire them. They already know.

Mama Nayo knows from the last days of her life when I watched the mainstream news with her during the Obama nomination process (and I hate the mainstream news, especially at election time) how I fed her dog (and I’m so allergic to dogs). Only for Mama Nayo. She knows from how I listened to her tell me about how she went into an old black woman’s kitchen on some voter registration activist mission and saw one of her very own broadsides up on the wall above the stove. And how she listened to this old black woman talking about how she reads this poem, this black-woman-self-love-everybody-better-know-it poem, not knowing Nayo, who wrote the poem, was standing right there. Saying “Yes. You know that poem girl? That’s my poem!” She said it and Nayo always remembered and gave it to me to always remember now. She knows from how I stood in line running errands at the oldest Black bank in Durham (Mechanics and Farmers) and the pharmacy dropping off checks and picking up the prescription that made her dying days less agonizing, embodying family so the teller and the pharmacist would both say: “You must be here for Nayo. Nayo’s people. Y’all sure do favor.” She knows from her place on my altar, in my heart, in all the air that surrounds me. She knows how happy I would be if one day someone compared me and my way and my work to her and her way and her brilliance.

Mama Nayo knows from the last days of her life when I watched the mainstream news with her during the Obama nomination process (and I hate the mainstream news, especially at election time) how I fed her dog (and I’m so allergic to dogs). Only for Mama Nayo. She knows from how I listened to her tell me about how she went into an old black woman’s kitchen on some voter registration activist mission and saw one of her very own broadsides up on the wall above the stove. And how she listened to this old black woman talking about how she reads this poem, this black-woman-self-love-everybody-better-know-it poem, not knowing Nayo, who wrote the poem, was standing right there. Saying “Yes. You know that poem girl? That’s my poem!” She said it and Nayo always remembered and gave it to me to always remember now. She knows from how I stood in line running errands at the oldest Black bank in Durham (Mechanics and Farmers) and the pharmacy dropping off checks and picking up the prescription that made her dying days less agonizing, embodying family so the teller and the pharmacist would both say: “You must be here for Nayo. Nayo’s people. Y’all sure do favor.” She knows from her place on my altar, in my heart, in all the air that surrounds me. She knows how happy I would be if one day someone compared me and my way and my work to her and her way and her brilliance.

And Mama Nia knows from the voicemail waiting on her phone right now, love messages early in the morning when we’re the only ones awake and on Facebook already. Tulsi everydayness towards balance, towards you do not have to do it all yourself. She knows that I praise the day we met in the street. How I cry every time that her way too talented son plays the drum or gets impossibly taller or writes a poem. How her daughter is a chosen sister who defends my life, love, and laughter, ready to take off her shoes and fight if she needs to. She already knows how honored I am to have been working beside her in classrooms, clearings, courtrooms, living rooms in so many organizations and coalitions and committees for the past seven years and for as long into the future as I can imagine. And since she too was mentored by Mama Nayo up to her very last day, she knows exactly that mentorship, and grandmentorship looks like exactly like love.

So this piece is not for Mama Nayo or Mama Nia, though they make it possible in my hands. This piece is for you. Because I want you to know. Especially those of you Ph.D. or tenure-pursuant Black feminists seeking mentors. I want you to know that my primary mentors here in my life who hold such sway over my decisions and the contents of my days, over what to write about and where to be, are Black women who were and are single moms using public assistance to free their time to free our people.

And I want you to know that because I want you to know that there is no bourgeois scarcity when it comes to Black feminist mentorship. It is no use fighting each other or feeling like we have to compete for one of five tokenized mentors at the top who may be so stressed out by interim chairing two programs and half of a department that they should not be holding the whole task of mentoring you anyway.

The more mentors we have, in more places, the better off we are, lest capitalism trick us into believing that only the well-funded, institutionally connected, socially secure Black feminist intellectuals have gifts for our sharp, critical anti-capitalist lifetimes.

The fact that my abundant ecology of living and ancestral mentors includes moms using public assistance, broke filmmakers, struggling trans kids, non-profit divas, barely not starving poets and more is what makes it possible for me to live untrapped every day with infinite options for useful and fulfilling love-fueled brilliance. This is what Audre Lorde meant when she pointed out that the only folks who are scared by the fact that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” are those who see the “master’s house (aka the university) as their only source of support.” Through practice and through the lives of my many mentors I know the academy is not the only nor the primary source of support for my brilliance and that the tenure track is only one of infinite paths that a Black feminist can choose to take.

I have the deep luxury of not measuring my impact, success, and purposefulness on funding, tenure, bills paid on time–and I want that freedom for you. Build a base of badass mentors that take different risks, make different sacrifices from each other, work in different conditions and with different styles. Affirm the fact that your Black feminist brilliance could lead you anywhere, not just further into ivory privileges. Let predictable sources write letters trying to find you. Get off the hook, like June Jordan.

Love,

Alexis

P.S. If you would like to be on the email notification list for ReMastered Brilliance, a new service I am starting to reconnect visionary underrepresented graduate students with their communities of accountability and a purposeful diverse ecology of brilliance, email me at brillianceremastered@gmail.com.